Here I’ve written mainly about Dan Evans’s book, A Nation of Shopkeepers, as the other book relates to the racial side of the frustrated white working class and the specific history of the US that causes the continuing rupture of white entitlement to their own detriment, taking down the whole working class with them.

In the past few months, I’ve been reading and thinking about how the UK welfare state came about and why most of the population was ready to vote in 1945 for such a radical departure from the previous basic selective insurance system of selective welfare and “laissez-faire” (leave alone) non-interventionist form of governance. This ultimately led me to ask who the swing voters were and why they changed from their former voting preferences.

And later, (1979) why they voted to end the post-war consensus. Though this was a far more gradual process, in reality, the choice at the time was a radical departure from the seemingly tired system of state dependence and employment to a self-employed entrepreneurial world of free market individualism, with little or no state intervention, well that is how it was sold.

So who on earth are these non-compliant working class? And why does the left continue to ignore/demonise this group?

According to Dan Evans (DE), the first issue is how we define ourselves in the context of class; to be working class is to ascribe certain cultural norms of birth, place, accent, cultural behaviours and consumption preferences. Your preference for Football or Rugby, your schooling and therefore networks. It is often said that your class stays with you no matter your rise or fall in society. In the UK, it goes beyond a statisticians definition; rather, it’s a badge to wear with pride, especially with the working class, to either show how x has risen from their ‘working class’ roots or ‘I may be wealthy, but at heart, I’m still working class’, etc.

So on this assumption, the working class would always vote for the working class political party, which post-1900 has been the Labour Party. A party whose roots came from the French Socialists and Marx’s observations concerning the exploitation of the working class by the feudal landlord and later the industrial bourgeoisie.

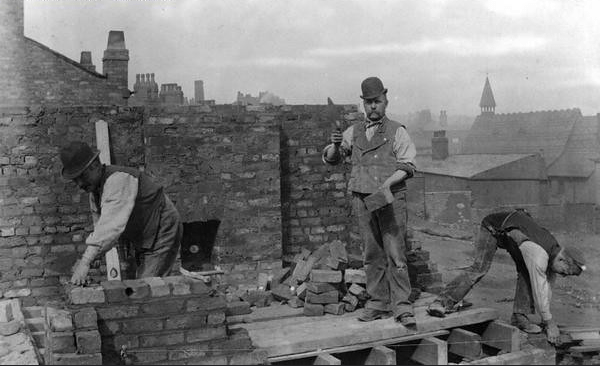

The new money does not come from inheritance and favours, but instead ‘owning the means of production’ and therefore being able to control the labour’s muscle power and take the ‘surplus labour power’ as profit, i.e. to earn subsistence, a labourer would need to work for say, 3 hours a day for 6 days if the capitalist pays them for the 3 hours, but to get that money they need to perform a further 9 hours per day for 6.5 days. All that labour power is given for free as a surplus, accessible to the capitalist, as the labourer no longer has agency; the capitalist owns the means of production in a sense, monopolises it. The labourer has to conform or starve (note; a very poor partial summary of Vol 1 Capital by Karl Marx); the capitalist is the bourgeoisie in this case.

To carry on with Marx’s observations, the Landowners were the old inherited money of the favours of Kings, who claimed money by mainly being rentiers of land to the wealthier peasantry, the rents determined by the productiveness of the land. The Borgiusise, as stated above, is the ‘new money’ from the inventiveness of the new industrialist exploiting the empire’s colonies’ natural resources and importing (cheap). Manufacturing and exporting as a monopolised market (expensive), using the latest ideas concerning free market economics of Adam Smith, Ricardo and Mill to justify the exploitation of labour ( if they don’t like the pay, they are a free agent to find work elsewhere, the reality was that the industrialists had formed cartels to keep wages down to subsistence levels calculated by others and/or how near to death they could exploit the workers) under the banner of the ‘natural laws of the market’ reaching a fair and just equilibrium, this of course was and remains a complete fallacy as proven by the dire working conditions of the unskilled industrial working class. The pretence was to counter the former corrupt idea of the mercantile system of hoarding wealth, to manipulate governments and countries via bribery and ‘favours’. In reality, the Mercantile system never went away. It just had a new cloak to disguise its true intent, namely to monopolise a market and then extract as much unearned (by the capitalist exploiting labour power) profit until the collapse of a market by oversupply or due to natural resource failures like a cotton crop (1860s), meaning mills would close due to the shortage of raw materials (which became known as the ‘business cycle’). The exploitation, extraction and lobbying government for trade advantages would continue until the outbreak of WW1.

At the top of the pile was the rentier Aristocracy, who owned vast sways of land by the gifts of Kings, then the new money of the capitalist industrial Bourgeoisie, and at the bottom of the pile was the waged Poloteriat, who had no political power as they owned nothing of any value (which determined your access to be able to vote as well as your gender); they were the former feudal peasantry, who had experienced some leverage thanks to the black death of the 14th Century, they had broken free (to a point) of their former feudal landlords and had some value due to their scarcity and the landlords not having the skills or intention to farm their lands. (note laws were passed by the landed to stop the peasantry from moving from landlord to landlord to trade up their price to the point of hanging).

Once the industrial revolution started to take hold, many went to the new industrial towns and cities looking for consistent rather than seasonal work. Industrialists had taken on board Adam Smith’s pin factory idea of the division of labour to de-skill the peasant artisan and thus have a surplus of unskilled cheap labour looking for work. With a ‘free market’ and the theory of French Physiocrats’ “laissez-faire” ( leave alone), the market could naturally find the ‘right price’ by the invisible hand of the collective consumer settling for a fair price.

The manufacturer, supplier and labour, via Adam Smith’s law of ‘supply and demand’, assumes (wrongly, as it turns out) that both sides approach with equal agency, power, honesty, transparency and within the law of the land then all will prosper in the long run.

Marx soon pointed out the fallacy of the natural law just by observing the working class conditions of health, life expectancy, education, agency and social and political standing (or lack of) of the 19th-century working class.

But there was another class that Marx dismissed as a grey area that he suggested would eventually be consumed by the more powerful class of the bourgeoisie or fall back to the proletariat. He called them the ‘Petty Bourgeoisie’ and Adam Smith Noted;

To found a great empire for the sole purpose of raising up a people of customers may, at first sight, appear a project fit only for a nation of shopkeepers. It is, however, a project altogether unfit for a nation of shopkeepers; but extremely fit for a nation whose government is influenced by shopkeepers.

— Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations

The Petty Bourgeoisie were typically small business owners, artisan skilled self-employed individuals, and a growing class of white-collar clerks working for accountants who owned their means of production but did not employ labour on a large scale. Many also became small-time rentiers owning one or two properties for rent as a pension in old age, as the only safety net was the 1830’s poor laws of the maligned and feared workhouses.

The Bourgisise, or the Proletariat, did not consume this class but adapted to the changing industrial landscape of the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. And this brings us full circle to the present Petty Bourgiese (PB).

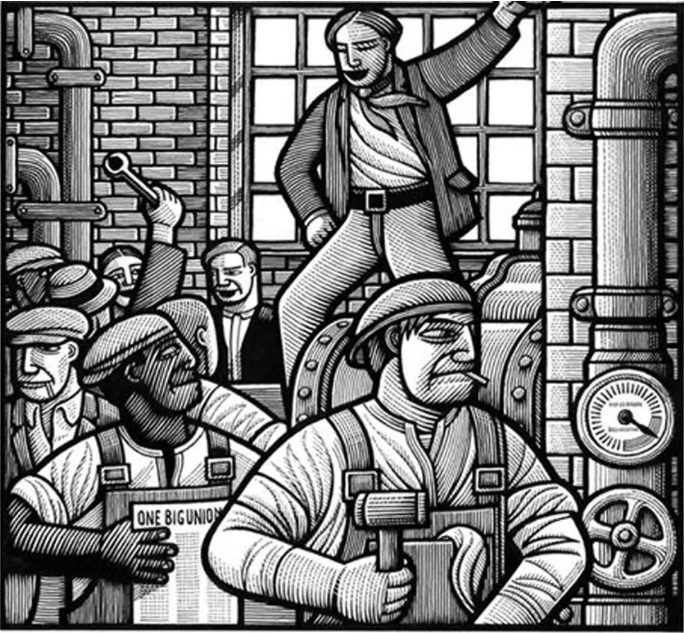

As a political group, they have traditionally been too small to gain a majority and thus would side with the traditional working employed class (ie the coal minors, for example) in voting Liberal (former Wig Party) who changed their name and identity to appeal to the ever-increasing via suffrage, working class. As the rise of a socialist movement increased amongst the masses of workers throughout Europe, the fear of an uprising meant the continued empowerment of the working class via suffrage, unionisation and basic selective welfare for the male productive worker in recognised employment. The PB were too distant from the halls of power to have an influence other than working with the traditional working class. This also included the new white-collar lower middle class who originally disassociated themselves on the grounds of class and not wanting to be associated with ‘trade’. However, they also started to unionise as the benefits of collectivism became clear.

Dan Evans first sees the power of the PB in the Russian Revolution’s struggle with how to place them as independent self-employed workers owning their means of production rather than the state. Lenin concluded they were too large a group to be ousted or crushed. Still, instead, they needed to be re-educated over the long period for the centralised form of socialism to work without a further bloody revolution. He felt that they infected the proletariat with ideas of individualism over the collective spirit needed amongst the proletariat to achieve the revolution’s goals. From my perspective, they proved that the seeds of individualism might be forced to lay dormant. Still, when the time and conditions improve just enough and like the pioneer plant species that initially break through the cracks of an abandoned space, they will rise and disrupt. Too much determinism within any political ideology has and will eventually lead to totalitarianism (which Keynes understood and wrote concerning Hayek’s book ‘A Road to Surfdom’ but ultimately suggested that the type of socialism the Labour Party of 1945 promoted was broad enough to retain entrepreneurial private industry albeit heavily regulated). The PB are always a thorn in the side of any country that adopts Communism as their businesses are too small and specialised to be overseen and regulated by the state. Therefore China, Cuba and even North Korea have a PB operating within their borders as free market traders.

So taking my former point, Dan Evans looks at the rest of early 20th-century Europe, which saw the Russian Revolution and the rise of the communist proletariat as a direct threat to the capitalist bourgeoisie and the gifted landed. What to do?

One of the answers lay in separating the PB from the Proletraiet and thus reducing their number. It came down to the fact that the proletariat owned nothing and therefore had nothing to lose. This starkly contrasted with the PB, who owned some property and their means of production, often owning or, with a mortgage, the place of production or land. Therefore they had something to lose and could be deterred from revolution via self-interest and the power of loss aversion. As faith was lost in parliamentary democracies to control and subvert the rise of the proletariat communist parties, the Bourgisise encouraged the PB to look to the nationalist interests of the individual rights to the ownership of the property over the communist ideal of the state owning all property. The rise of fascism amongst the PB was a counter to the loss of personal property rather than an ideological standpoint. Antonio Gramsk, in his article of 1921 called; The Ape of the People’ argued that Fascism was the first movement to organise the PB into a political force with a counter-revolutionary purpose to defend property and capitalism over communism.

The PB were not at the forefront of fascism; rather, they were used as foot soldiers by the more powerful vested interests of the bourgeoisie and landed. Fired up by othering, nativism (simplicity of the rural tradition of time-honoured annual agrarian certainties) and nationalism, the boundaries of what is justifiable to the greater good get distorted as the rise of the mob reaffirms its existence by the simple propaganda of right is on your side, deferring responsibility to the authoritarian power of dictatorial leadership. The PB comprised what Evans calls the old PB of the skilled artisan and shopkeeper and the new PB of the white-collar worker who, for the first time, were experiencing high unemployment.

But it should be noted that the PB in the UK and the US did not rise in such a manner. The extreme situation post WW1, the collapse of the Treaty of Veasllie, left the void for, as Keynes predicted, would lead to populist leaders filling that void with nationalism under the banner of ‘taking back control (sound familiar)?’

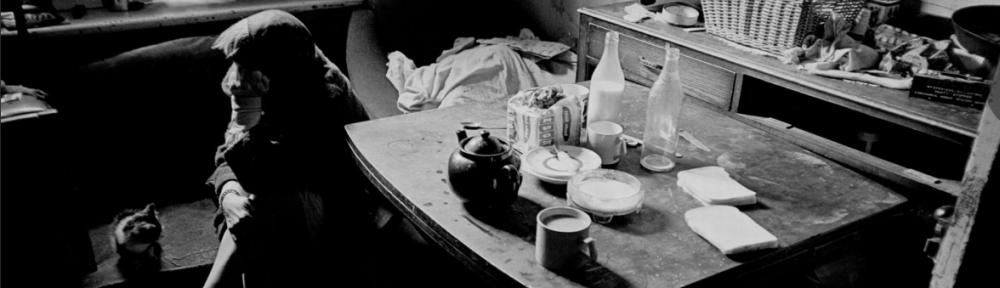

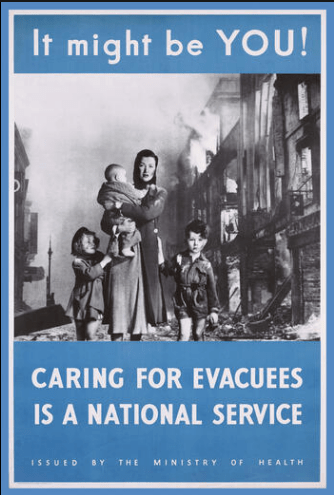

Post-WW2, the PB in the UK and US sided with the proletariat, as they fought side by side. In the UK, the evacuation of children from the cities to the wealthier parts of the country shone a light on the depravity of the working class whose children were malnourished, poorly educated and suffering from diseases of overcrowding and little or no health care. Such was the state of malnutrition that a national campaign was organised to ensure the children were fed first. The agrarian PB and the middle and upper classes would have witnessed this.

The PB also suffered like the working class in the 1930s, with business losses through the inaction of the British Government of the day, leading to bankruptcy; unlike the US New Deal of intervention of the 1930s that quickly returned the US to prosperity, the British government stuck firmly to “laissez-faire” (leave alone) principles of non-intervention in fear of making matters worse. In hindsight, this was the wrong move, as proven later by the post-1945 Keynesian intervention model. The 1945 Labour Party entered the 1945 election promising to fulfil the popular 1942 Beveridge report, which was based on universal care, not selective, as was the case from the basic support offered by the early 20th century Liberal Party and Conservative Party of the 1940s

The often cited mantra of ‘We won the war, now let’s win the peace’ was the overwhelming post-war consensus that Churchill misread, leading to the Tory collapse in the 1945 election. All classes had fought and died together, manned the pumps, made the armaments, dug the land, and washed the sick. Even social housing was based on the Labouerer, the Butcher and the Docter living comfortably together in highly specified housing with ample room and two internal toilets (as proposed by the later Housing Minister Nye Bevan).

From 1945-1975, the political post-war consensus of heavily regulated capital policy, high wealth taxes on high incomes, capital and inheritance meant that unearned income from capital that the capitalist/reinter was reduced so that intergenerational accumulation was also reduced, ultimately meaning that each generation made their way, by contributing to society with productive labour instead of the rentier period of unearned inheritances of pre-WW1. The idea of a more equal and egalitarian society reduced the gaps between the employed blue-collar worker and the self-employed PB, as well as the rising white-collar middle class.

All of this is perfectly summed up in the 1960s sketch on ‘That Was the Week That Was’ a satirical weekly comedy sketch show on the BBC; this sketch is about class (see below) is a good reflection of the time and how times had changed from the early 20th century.

Note how the upper class had lost their money due to high taxes and death duties, and the PB middle had all the money, and the worker, as usual, ‘knew his place’. But this was still within the post-war one-nation Tory consensus of accepting and funding the welfare state as it was seen as a benefit to all, and to attack it would’ve been political suicide.

The PB of the period was relatively small as many artisans worked for medium businesses as work was plentiful and starting a business was too bureaucratic. The new white-collar PB were more educated due to free university with grants provided for the low-income families and tended to vote as per their type of posting; the left was no longer just the home of the working class but increasingly of middle-class graduates, changing the left to what later Thomas Picketty referred to as the Brahmin Left (the Brahmin being the intellectual cast of Indian tradition).

“So what changed, and why did the PB turn against the left and now reside on what Thomas Piketty calls the Mercantile Right (meaning trade over higher education)”?

By the mid-1970s, the allure of centralised government, knowing what was best in the eyes of the old and new PB, had failed. They saw the country held to ransom by the employed unionised state worker whilst they felt derided as a class thanks to movies like Peter Sellers I’m Alright Jack, where the shop steward seemed to control the PB by union power backed up by the state.

Enter stage right Margret Thatcher with Friedrick Von Hayek’s book, A Constitution to Liberty, stuffed in her handbag.

Her appeal to the frustrated PB meant they swapped from supporting the working class proletariat to the bourgeoisie. The promise of the Right to Buy (former council houses), deregulation, and more support rather than derision for small businesses felt like a clean sheet, a chance to break free of the shackles of big government; well, that was how it was sold as the sunny uplands. The post-war consensus was over.

Dan Evans rightly does not condemn the PB but rather asks why we deride the class, even though we all benefit from them; they build, maintain and service our houses. They sell the goods we fill our houses with; they take the hardest hits as they are self-employed (ie Covid, self-employed screwed, so carried on working finding key worker work, ie delivery services) when the economy goes bad.

Like the former elites of the past, we ignore the PB at our peril. At present, due to their property, clever mercantile ways will exploit every way possible to get ahead. Most have a point to prove:

“I may not have a degree, but I’ve already paid off the mortgage and have a ‘Beemer on the drive’ and a few Rental properties, and your flipping burgers with a Master’s in humanities and 50K of debt, remind me, whose the intelligent one”?

White Van Man (old PB), Modeao Man (New managerial PB). So what is the battleground now?

The under-40 educated renters who are part of the New PB, the parents of this group who are now expecting a Bank of Mum and Dad to help out, Intergenerational tension as the under-40s see hundreds of thousands of pounds locked up in grannies once cheap but now expensive property.

“We have gone from state welfarism to asset welfarism; great, unless you don’t have access to an asset, you are screwed and at the mercy of your free market unregulated landlord”.

Parents see their children unable to afford rent and not wanting to produce grandchildren for fear of the future.

The answer; Look north to the land of the Nordics (a later essay), the land of Viking Economics, the Law of Janteloven and a popular and supported State Welfare system.