The best tactic for hiding the biggest scams.

Overview

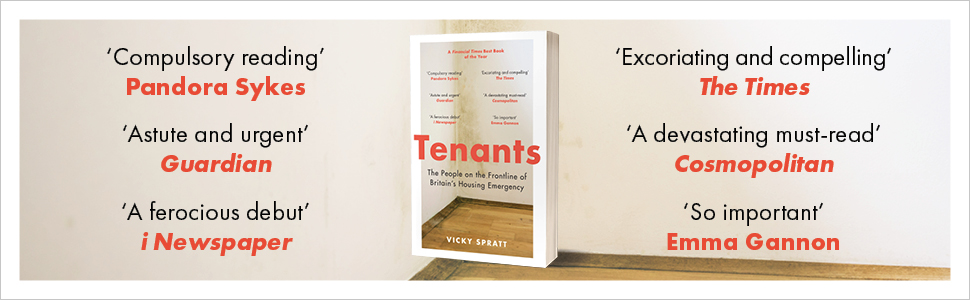

This post came about when I realised that sometimes it’s better to communicate a concept using fiction and games rather than the often dull route of academia that few ever read. The game was obvious, but the book came from a green flash of inspiration; on further research, I found I was on the right track. This further led to why and what the authors’ ideas were promoting. Below are some explanations and further thoughts on why these ideas from 1900 are more relevant than ever.

1900; the same issues as the 2020s

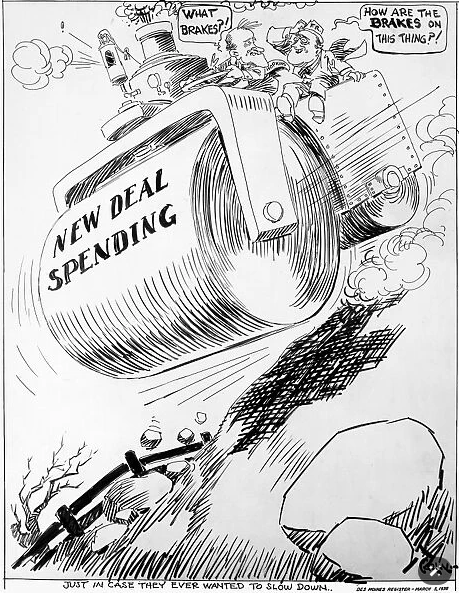

Suppose an idea or concept is large enough to become a norm, accepted by society by familiarity, and eventually a cornerstone of societal norms.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, two people noticed two norms that did not seem to add up: one was a playwright and journalist, and the other was an inventor, poet, engineer, and journalist.

Both saw an issue with money in its creation and use. One used a children’s book as an analogy to the money system, the other a children’s game in which the goal was to bankrupt all your opponents.

Both became classics and remain so to this day. The analogy behind both has been lost, but the truth of their criticism remains in plain sight.

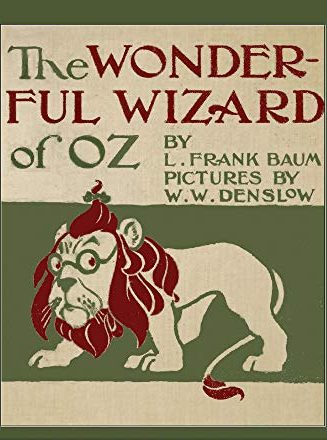

If you have yet to guess, the children’s book is The Wizard of Oz, written by Lyman Frank Baum (1856 -1919), first issued in 1900 in the US.

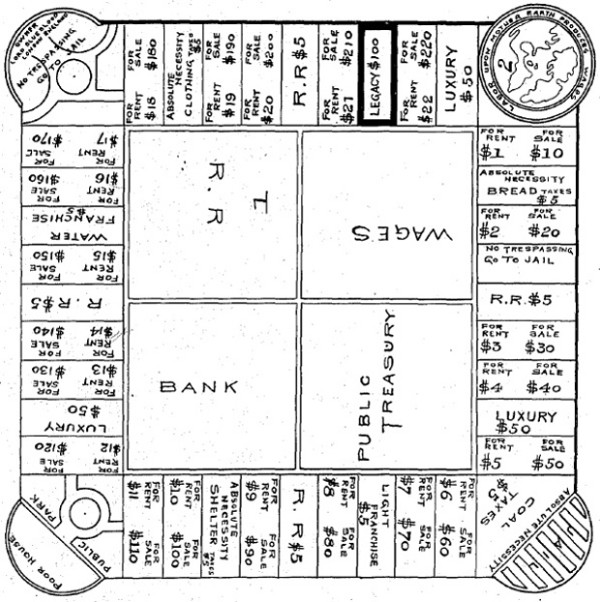

The game is a board game called The Landlords Game, invented by Elizabeth J. Magie (1866 -1948) in 1903, later to be renamed (ironically) Monopoly by James Darrow, who sold the rights to Parker Brothers, who gained the monopoly of the game in 1935 (also paying E. Magie a paltry $500 for the copyright of The Landlords Game)