Further analysis of where Vicky didn’t go!

My comments on the interview and replies to other’s comments are in parts two and three.

I’ve been researching housing unaffordability for seven years and am about to start writing a dissertation on Rent Control (℅ Dr Anna Minton). After all these years of trying to find solutions, the elephant in the room is Rent Control. Why?

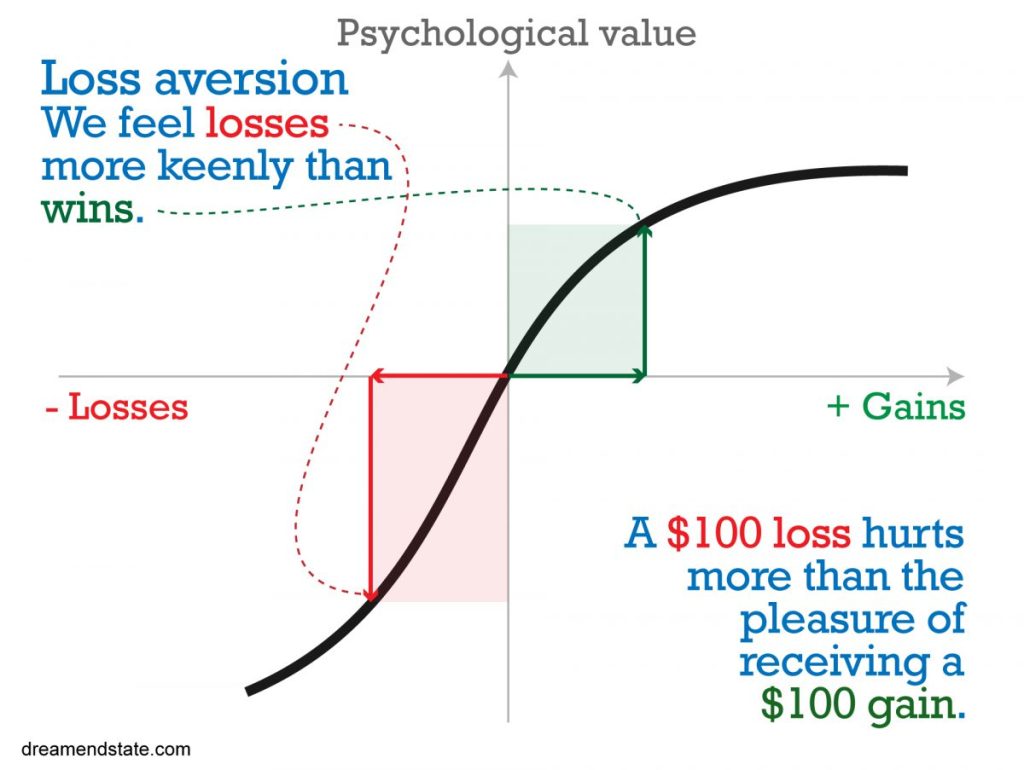

Because it gets right to the heart of the issue, which is, in fact (drum roll)… land values.

This is a disappointing and slightly dull answer, but it’s one of the keys that has unlocked many doors for working—and middle-class people who don’t want to spend 30-50% of their income on a 40-year mortgage or rent to a landlord.

Some of the main authors to thank for this conclusion are John Doling (tries to be neutral), Danny Dorling (left), Nick Bano (left), Kemp (right), and Christine Whitehead (LSE, right). It is always good to see if there is a counter-argument of value—there isn’t.

(As well as Smith, Ricardo, Marx, Keynes, Piketty, Blyth, Mazzucato, Christophers, Kelton, Richard Murry and Minton)

Why? An example: I’m a former bricklayer who ran a business in construction, so I know about house building pricing. My humble little flat;

In 1994, it was purchased for £47,700 with a floor area of 42m². In 1994, it cost £600 per m² to build, thus £25,200 to rebuild. Therefore, 53% build/47% land value = £47,700.

Now (without all the breakdowns), it’s 33% build/67% land value! @£250K purchase price (based on £2K/m² rebuild).

The killer point: in the 1950s, land values of new builds dropped to 3%. Based on those values and present-day build values (£2K per/m²), my flat would be on the market for £86,600, which equates to 2.4 times the full-time national average income (£35K). 2.4 times was also needed in the 1950s-60s for a single average income to buy an average 2.5-bed semi (.5 being the box room).